The Doctrine of Corporate Veil and Its Exceptions: A Legal Analysis

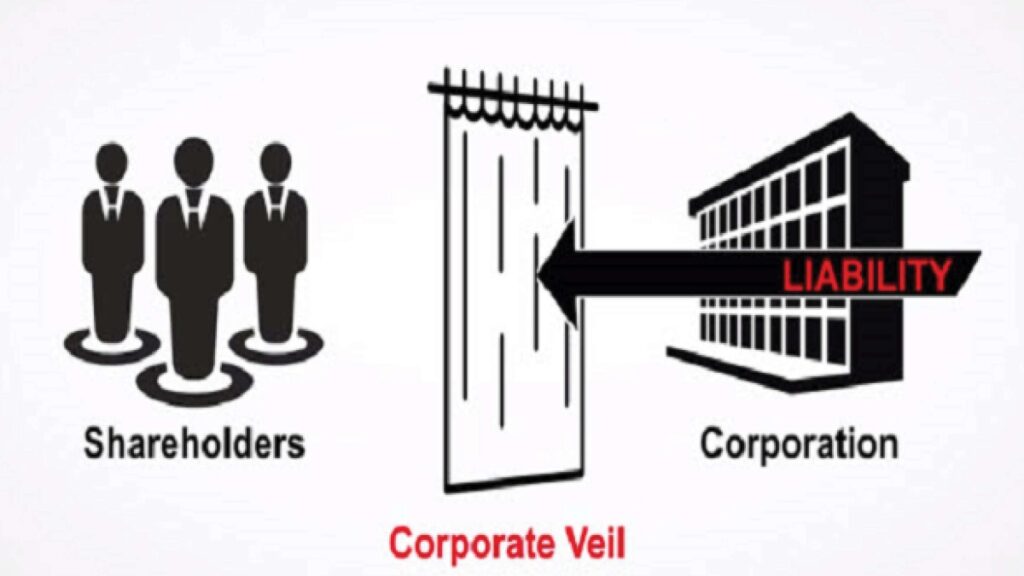

Introduction The doctrine of the corporate veil is a foundational principle in corporate law, where a company is treated as a separate legal entity distinct from its shareholders, directors, and employees. This legal concept provides that the company’s obligations, debts, and liabilities are its own, protecting the personal assets of the individuals behind the company. However, there are circumstances under which the courts may “pierce” or “lift” the corporate veil, thereby holding the individuals behind the company personally liable. This article explores the doctrine of the corporate veil, its importance in corporate law, and the various exceptions that allow for its piercing. The Doctrine of Corporate Veil The corporate veil refers to the legal distinction between a company and its shareholders or directors. This concept is rooted in the landmark case of *Salomon v. Salomon & Co Ltd* (1897), where the House of Lords held that a company is a separate legal entity from its owners. This principle has been instrumental in encouraging entrepreneurship, as it limits the financial risk of shareholders to the amount of their investment in the company. The corporate veil serves several purposes: Limited Liability: Shareholders are not personally liable for the debts and liabilities of the company beyond their shareholding. This encourages investment and economic growth by reducing the risk associated with business ventures. Perpetual Succession: The company continues to exist even if the shareholders or directors change or pass away. This ensures stability and continuity in business operations. Separate Legal Identity: The company can own property, enter into contracts, sue, and be sued in its name, further reinforcing its status as a separate entity. Piercing the Corporate Veil: Exceptions to the Doctrine Despite the protection offered by the corporate veil, courts have recognized situations where this veil can be pierced. The following are some of the key exceptions where courts may hold the individuals behind the company personally liable: Fraud or Improper Conduct The most common ground for piercing the corporate veil is fraud or improper conduct. If a company is used as a vehicle for committing fraud or engaging in unlawful activities, courts are more likely to hold the individuals responsible. For instance, in the case of Gilford Motor Co Ltd v Horne (1933), the court pierced the corporate veil to prevent a former employee from using a company he formed to circumvent a non-compete clause. The court found that the company was a mere façade used to perpetrate a fraud. Sham or Façade Companies A company that is merely a sham or façade, created to avoid legal obligations or to shield individuals from liability, may not be entitled to the protection of the corporate veil. In *Jones v Lipman* (1962), the court pierced the corporate veil where the defendant transferred property to a company to avoid a contract for sale. The court found that the company was a sham and ordered specific performance against the defendant. Agency or Alter Ego Theory In certain cases, courts may pierce the corporate veil where the company is acting as an agent or alter ego of its shareholders. This occurs when the company is so closely controlled and dominated by an individual or group that it lacks a separate existence. The alter ego theory was applied in the case of DHN Food Distributors Ltd v Tower Hamlets (1976), where the court treated the parent company and its subsidiaries as a single economic entity. Undercapitalization If a company is inadequately capitalized from the outset, with insufficient funds to meet its obligations, courts may pierce the corporate veil. Undercapitalization suggests that the company was never intended to operate as a separate legal entity but rather as a shield for its owners. In such cases, courts may hold shareholders personally liable for the company’s debts. Avoidance of Existing Obligations Courts may also pierce the corporate veil where a company is used to avoid existing legal obligations. For instance, if a person transfers assets to a company to avoid paying a debt or judgment, the court may disregard the corporate entity. In *Adams v Cape Industries Plc* (1990), although the court did not pierce the veil, it established guidelines for doing so, noting that the corporate structure should not be used to avoid existing obligations. Public Policy and Justice In some instances, courts may pierce the corporate veil on grounds of public policy or justice. This is often seen in cases involving tort liability, environmental damage, or human rights violations, where the interests of justice demand holding the individuals behind the company accountable. The case of Chandler v Cape Plc (2012) illustrates this, where the parent company was held liable for the asbestos-related injuries of an employee of its subsidiary on public policy grounds. The Legal Implications of Piercing the Corporate Veil Piercing the corporate veil has significant legal implications for the individuals involved and for corporate law in general. It undermines the fundamental principle of limited liability, exposing shareholders and directors to personal liability. This can have a deterrent effect on business ventures, as individuals may be less willing to invest in or manage companies if they risk personal liability. Moreover, piercing the corporate veil can lead to complex legal battles, as courts must carefully balance the need to uphold the principle of limited liability with the need to prevent abuse of the corporate structure. The decision to pierce the veil is often fact-specific, requiring a thorough analysis of the company’s activities, the intentions of its shareholders, and the overall context. Conclusion The doctrine of the corporate veil is a cornerstone of corporate law, providing essential protection to shareholders and promoting economic growth. However, this protection is not absolute. Courts have developed a range of exceptions that allow them to pierce the corporate veil in cases of fraud, sham companies, undercapitalization, and other improper conduct. While these exceptions are necessary to prevent abuse, they also carry significant legal implications, particularly in terms of personal liability for shareholders and …

The Doctrine of Corporate Veil and Its Exceptions: A Legal Analysis Read More »